BIOGRAPHY

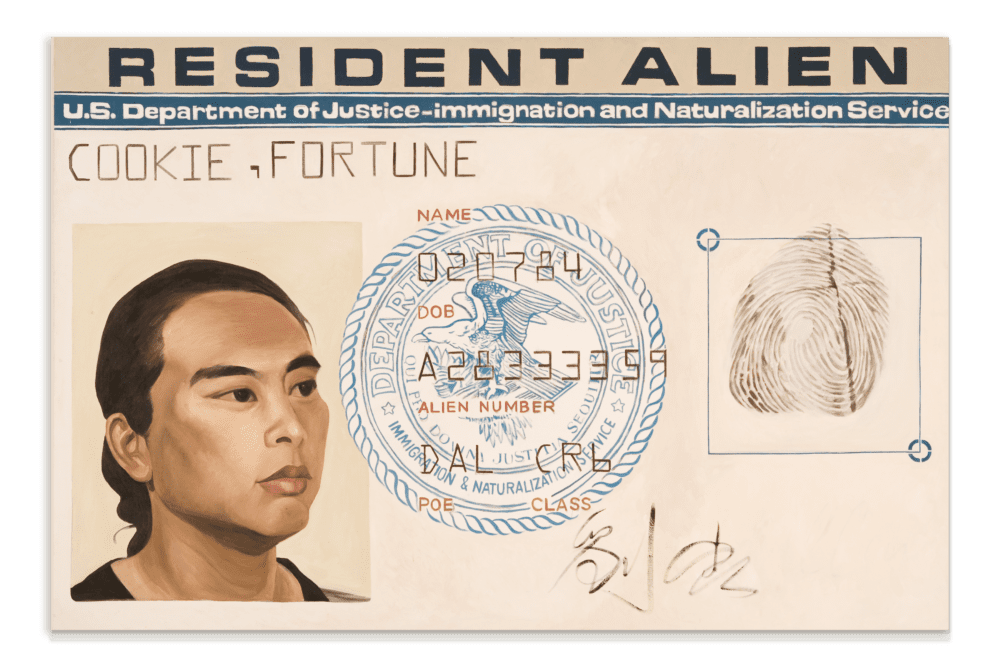

Hung Liu (b. Changchun, China, 1948 - d. Oakland, California, 2021) was a groundbreaking contemporary artist known for her powerful paintings based primarily on historical Chinese photographs, and her installations addressing the racial and cultural complexities she witnessed upon immigrating to the United States at the age of 36.

Liu came of age under the communist regime of Mao Zedong and was profoundly impacted by the Cultural Revolution. At the age of 20, she was sent for proletarian “re-education” in the countryside. There, she worked in rice and wheat fields for seven days a week for four years. She learned how to operate a camera and took to sketching and drawing her neighbors and fellow villagers: an act of artistic and personal self-preservation that was foundational throughout her life and career. In 1979, she was admitted to the graduate program at the Central Academy of Fine Art in Beijing, where she majored in mural painting. Throughout her official art education in China, she was instructed to paint within the Socialist Realist style, which would remain influential to her practice for many years to come.

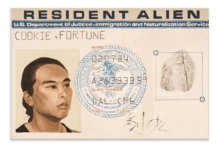

1984 was a landmark year for Liu: after years of campaigning for permission to leave China, she arrived in the United States to begin graduate studies at the department of visual arts of the University of California, San Diego. She studied under Allan Kaprow, the American originator of Happenings. The new creative freedom she experienced upon arriving in the U.S. and her exposure to fellow students and peers such as artists Lorna Simpson and Carrie Mae Weems, as well as critics and theorists Moira Roth and Jeff Kelley (her future husband), invigorated her conceptual thinking.

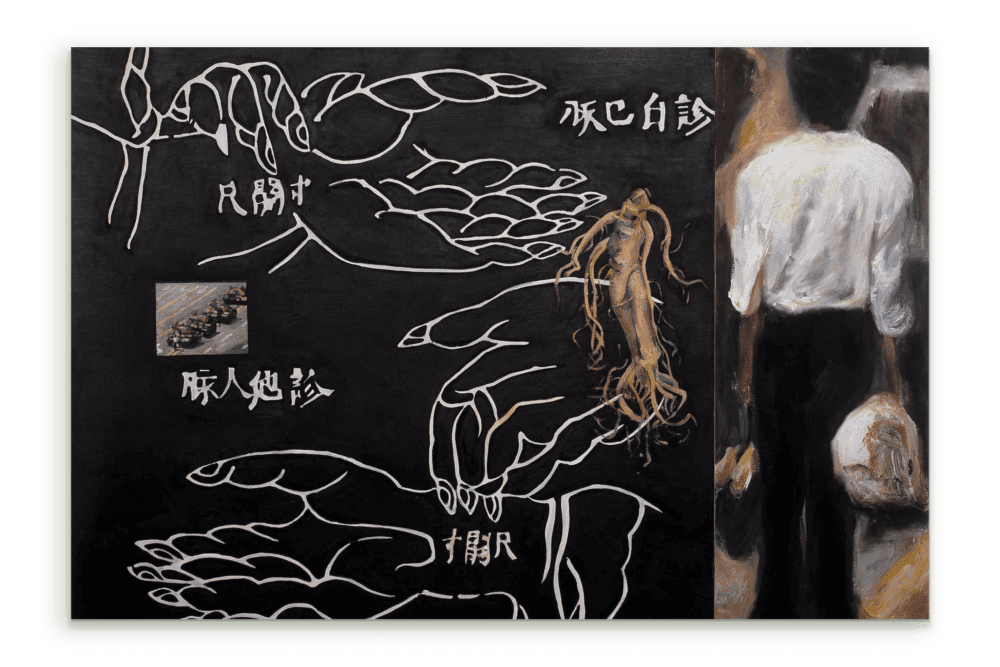

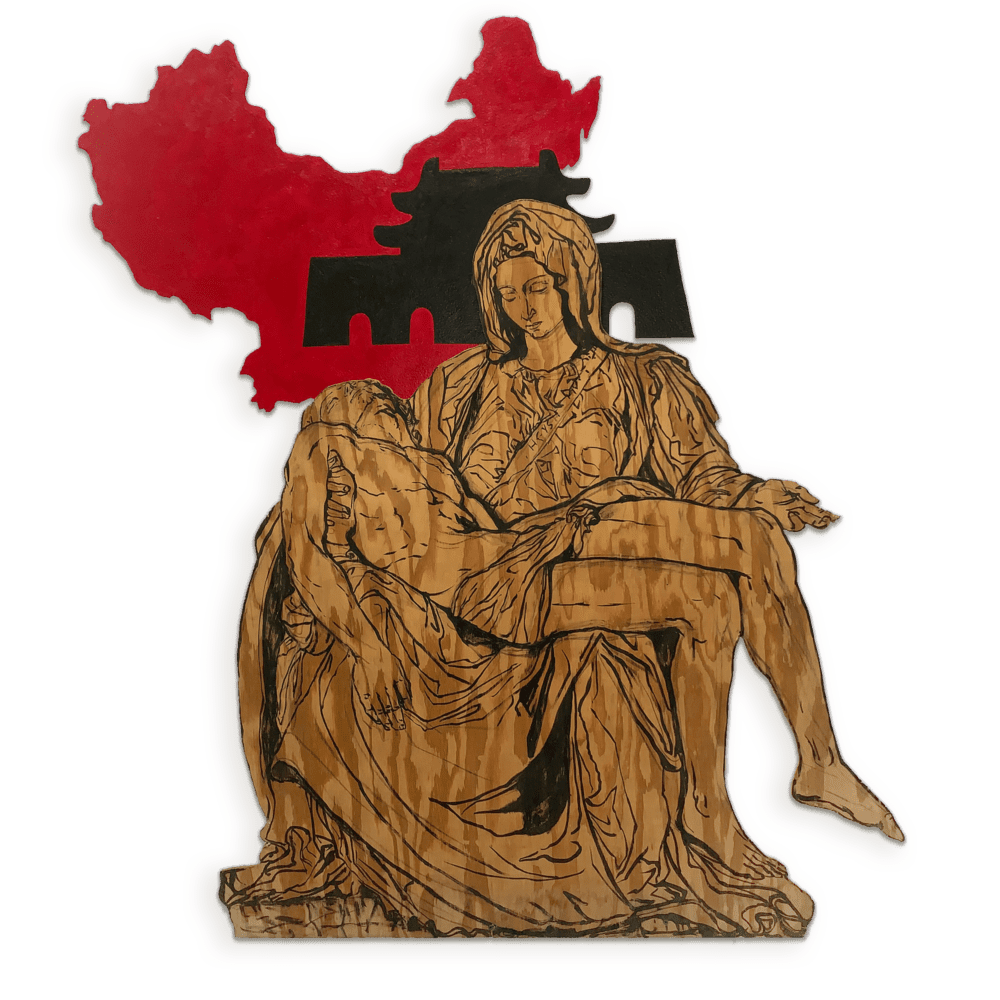

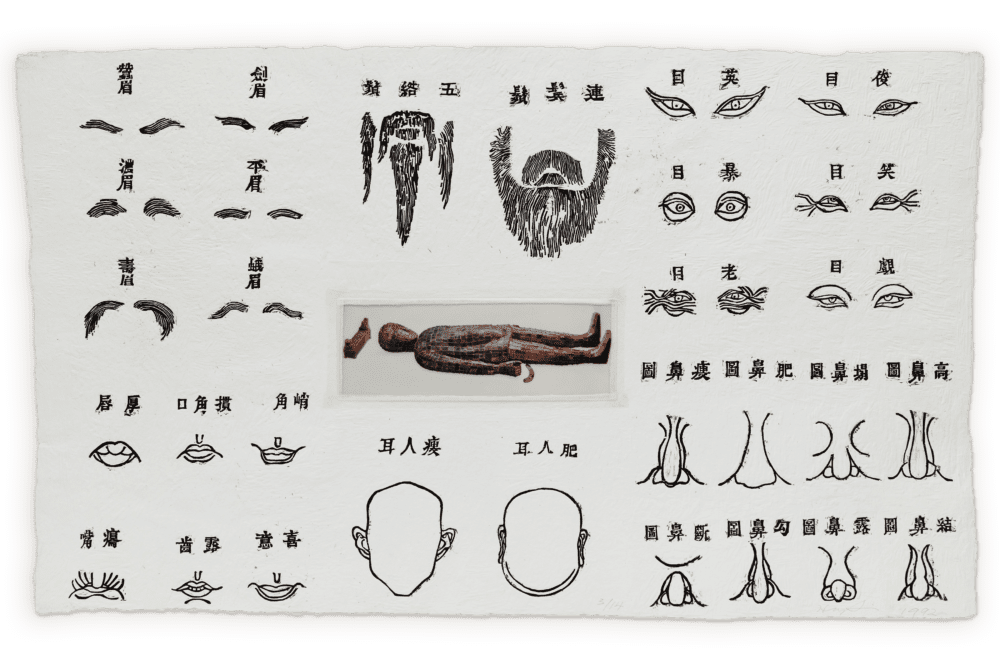

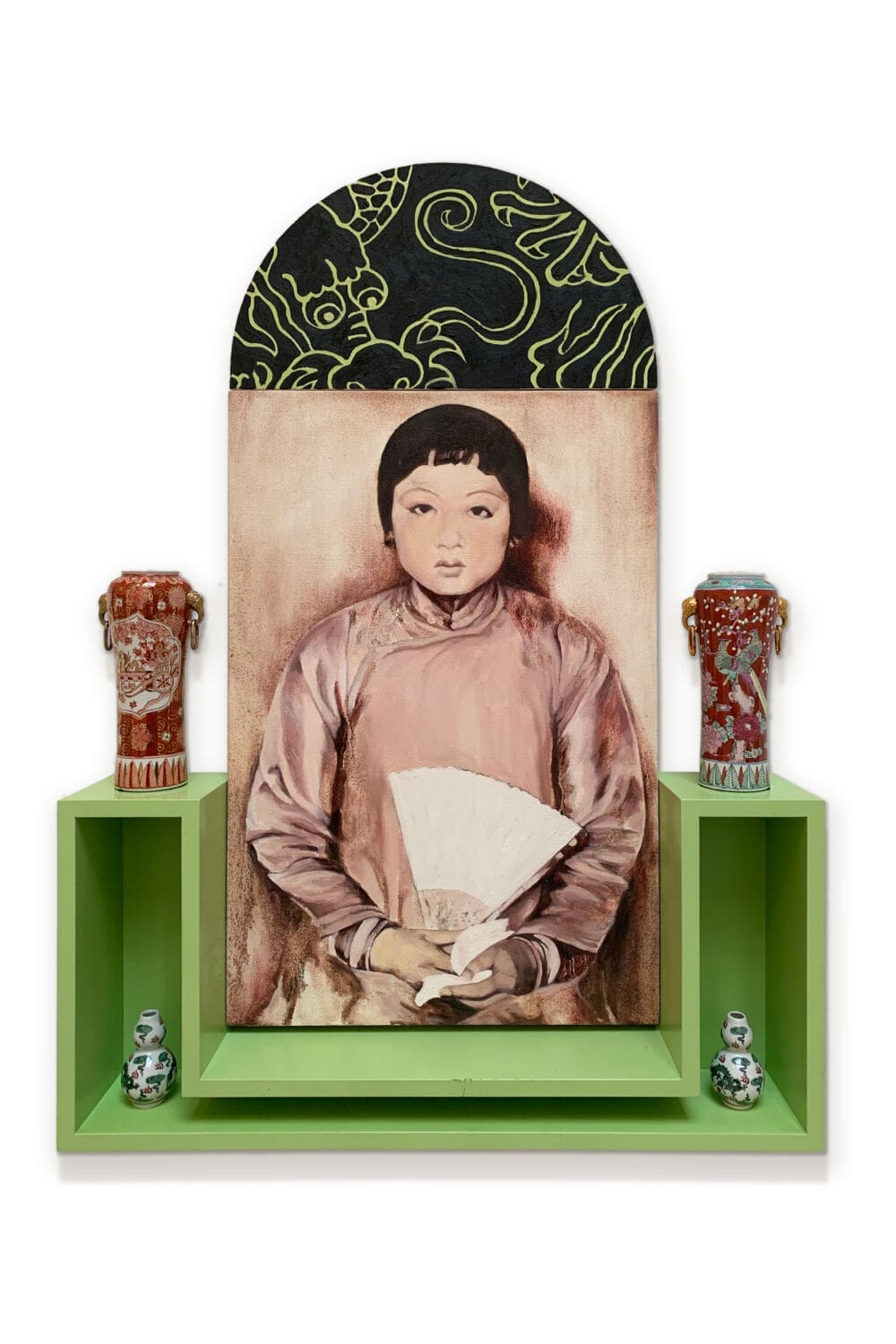

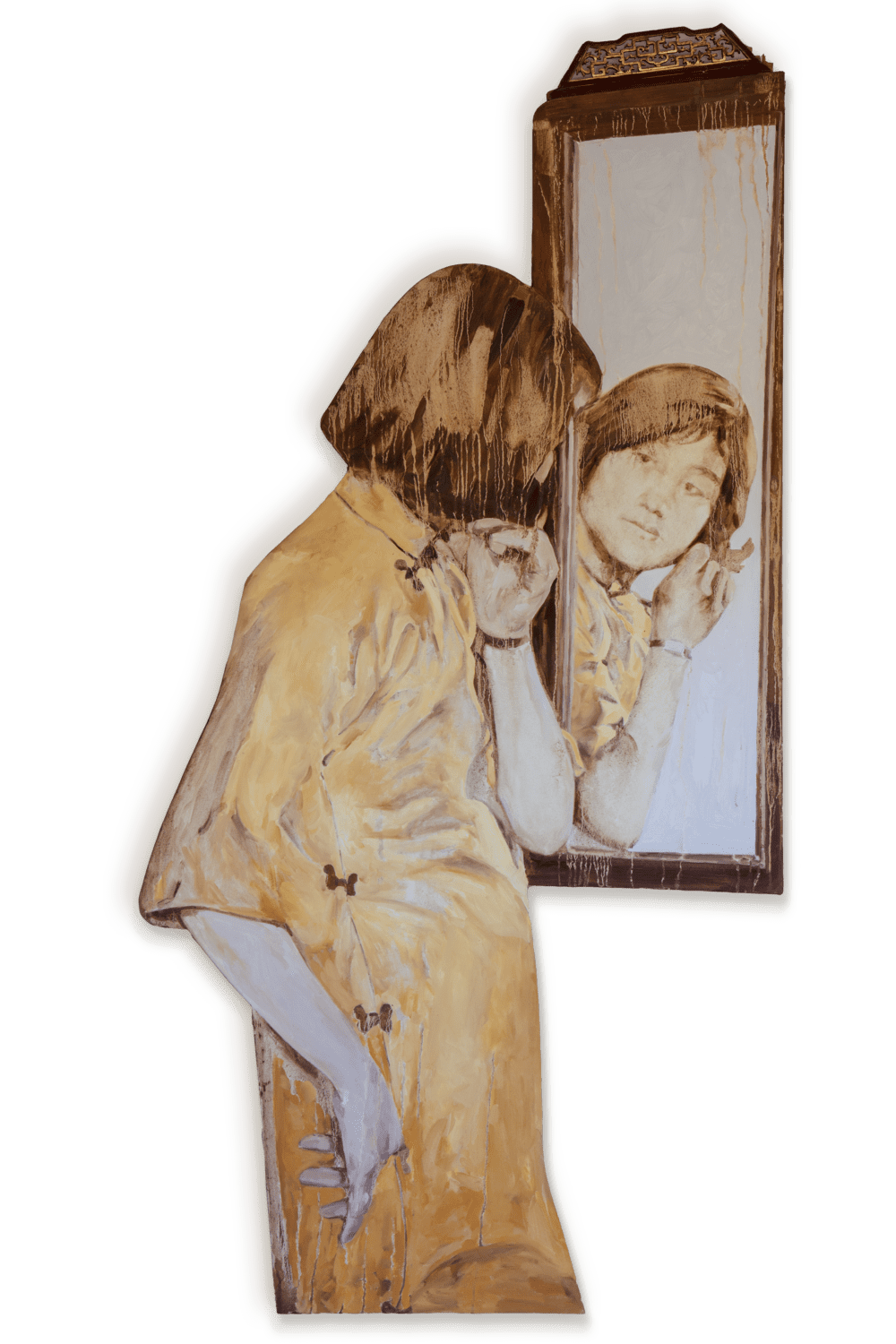

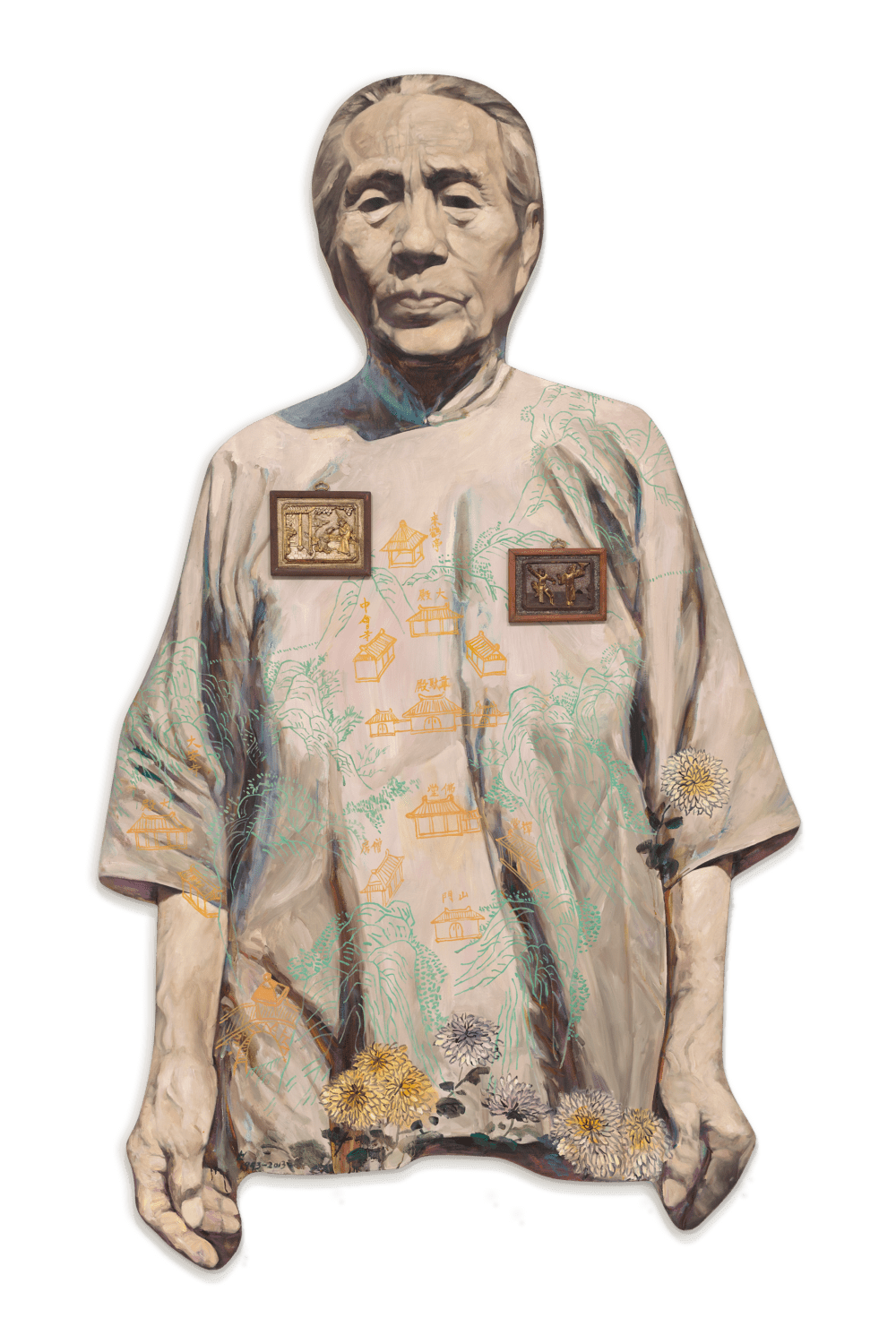

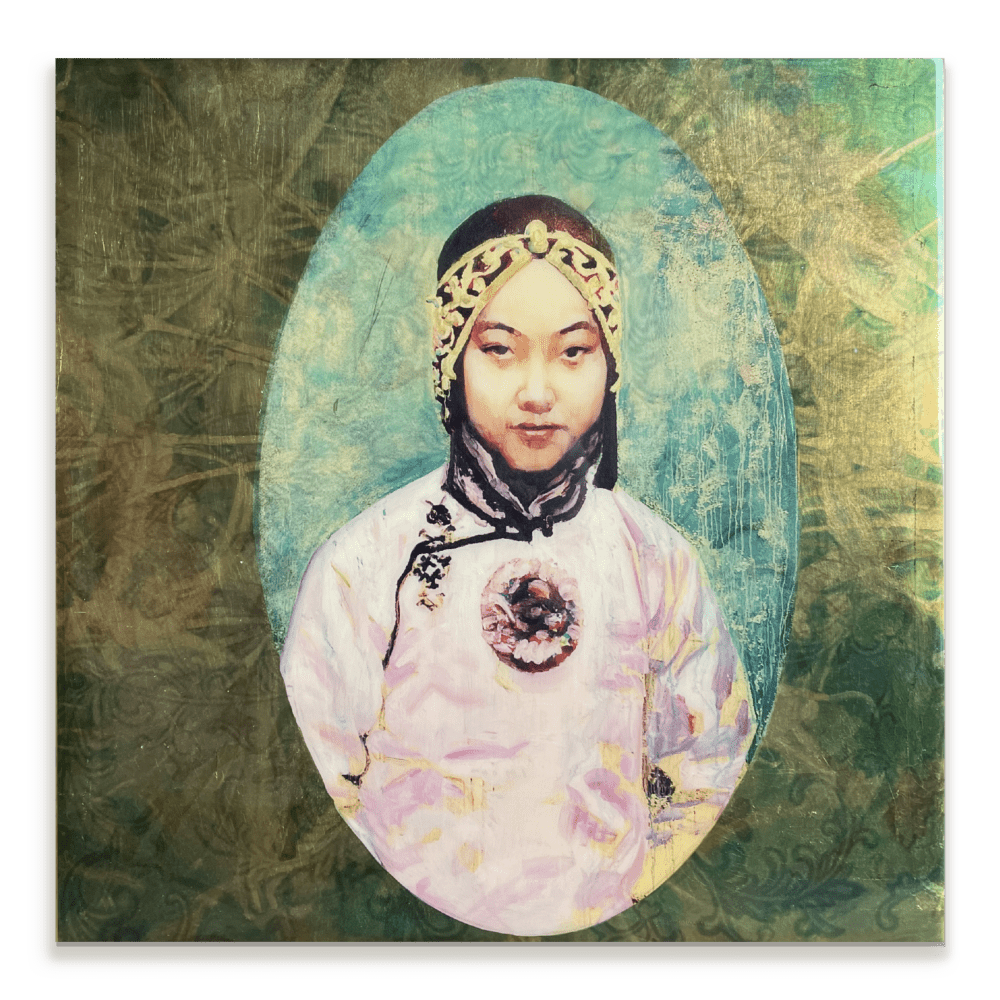

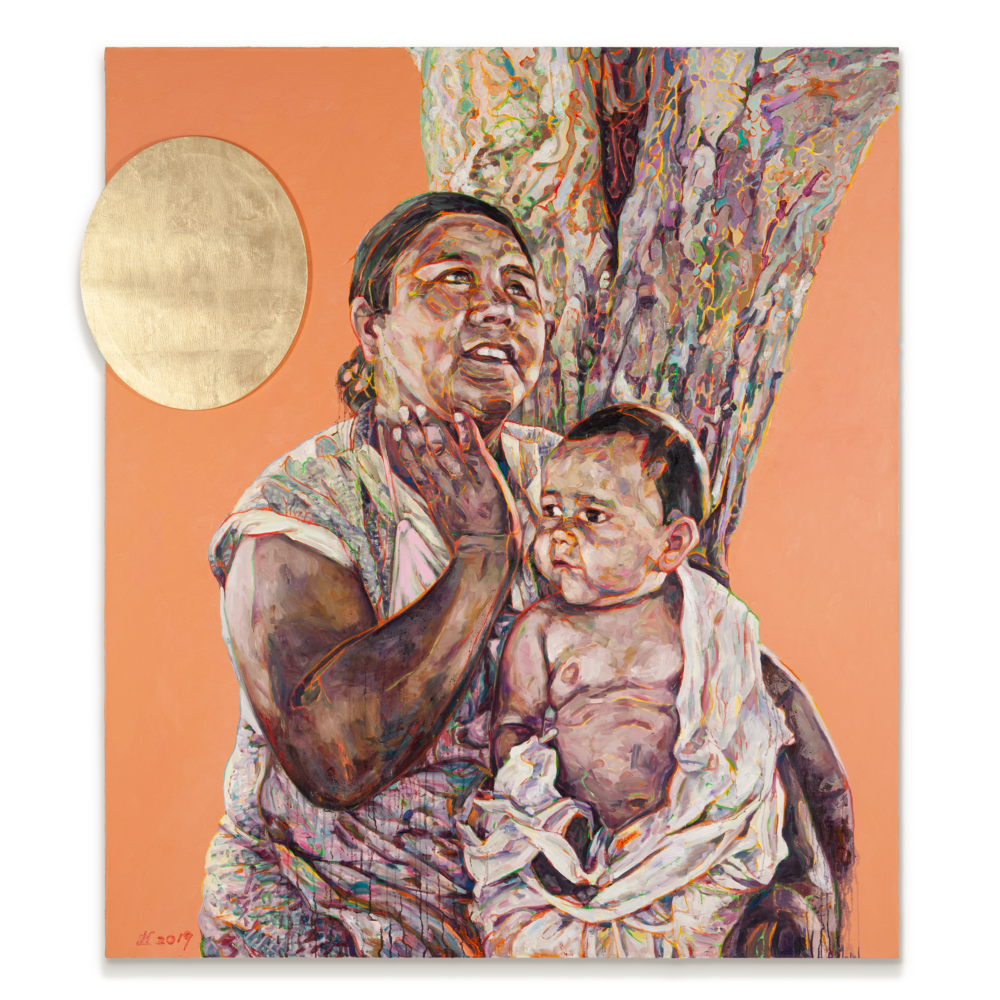

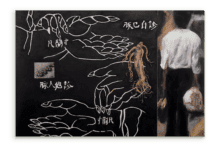

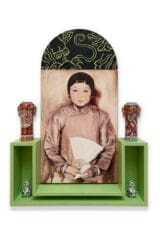

Interested in the political tensions between the so-called objective truths reflected in a photograph versus the mediated vision in a painting, Liu began using photography in her painting practice in the mid-1980s. Further, her background in murals combined with the explosion of conceptual art she was exposed to in California resulted in immersive, multimedia presentations of her work, bringing in objects, fortune cookies, Chinese temple money, and abacuses to underline her message. The mingling of disparate visual, conceptual, political, and artistic influences that Liu was exposed to throughout her career resulted in novel ways of making art: conceiving of each artwork as an object, Liu worked with shaped canvases and installations to lend a multi-dimensional—even shrine-like—aspect to her work.

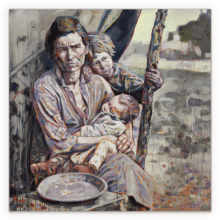

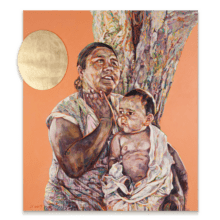

Liu’s monumental portrayals question the veracity of photography and historical imagery. Her subjects over the years have included prostitutes, refugees, street performers, soldiers, laborers, and prisoners, among others. Much of the meaning of her painting comes from the way the linseed oil washes and drips dissolve the authority of the documentary images, suggesting the passage of history into memory. Liu has invented a kind of weeping realism that surrenders to the erosion of memory and the passage of time while bringing faded photographic images to life as rich, facile paintings. She summons the ghosts of history, turning old photographs into new paintings.“I hope to wash my subjects of their ‘otherness’ and reveal them as dignified, even mythic figures on the grander scale of history painting,” Liu explained.

Around 2015, Liu shifted her focus from Chinese to American subjects. By training her attention on Dorothea Lange's displaced individuals and wandering families of the American Dust Bowl, Liu found a familiar landscape of overarching struggle and underlying humanity, having been raised in China during an era of epic revolution, tumult, and displacement. These paintings departed from her known fluid style. Instead, this series of works were reconceptions of Lange’s photography, their webbing of colorful lines, which she described as “topographical mapping,” connecting the subjects to the land while weaving through struggle and history.

A trailblazer, Liu was a peer to such leading artists as Enrique Chagoya, Carrie Mae Weems, Mel Chin, Judy Chicago, Lorna Simpson, Liu Xiaodong, Yu Hong, Lin Tianmiao, and Wang Gongxin, among others. Ai Weiwei, who she met in China in 1979, has written that she is “One of a kind.”

In 2023, Liu’s work was the subject of a exhibition at the San Francisco Museum of Modern Art, titled Hung Liu: Witness. In 2021, the Smithsonian’s National Portrait Gallery organized Hung Liu: Portraits of Promised Lands, a retrospective look at the artist’s portraits. Curated by the museum’s former curator of painting and sculpture Dorothy Moss, this was the first solo show by an Asian American woman in the museum’s history. Liu died of pancreatic cancer just three weeks before the show opened in Washington. Liu’s work is currently the subject of Remembering Artist Hung Liu at the Oakland Museum of California.

In 2013, the Oakland Museum of California organized Summoning Ghosts: The Art and Life of Hung Liu, which traveled through 2015. In a review of that show, The Wall Street Journal called Liu “the greatest Chinese painter in the U.S.” A two-time recipient of the National Endowment for the Arts Fellowship in painting, Liu also received a Lifetime Achievement Award in Printmaking from the Southern Graphics Council International in 2011.

Liu’s works have been exhibited extensively and collected by the Asian Art Museum of San Francisco, CA; Los Angeles County Museum of Art, CA; Metropolitan Museum of Art, NY; Museum of Modern Art, NY; National Gallery of Art and the Smithsonian’s National Portrait Gallery, DC; San Francisco Museum of Modern Art, CA; and Whitney Museum of American Art, NY, among others. At her death, Liu was Professor Emerita at Mills College, in Oakland, California, where she taught since 1990.

All image of artwork ©️ Hung Liu Estate/Artists Rights Society (ARS), NY.